Bringing private markets to the masses is the talk of the investment world these days. As more capital formation takes place beyond public exchanges, efforts are underway to give retail investors access to private equity and private credit. Semiliquid funds offer one route. Private assets may even be coming to 401(k) plans.

Skeptics suspect a cash grab. As much as phrases like “democratizing access” sound altruistic, private market investment managers see retail assets as a means of growing their businesses. Private market funds are known for high fees, illiquidity, and opacity. Their diversification and performance benefits can be oversold.

Even for investors with no interest in private markets, though, it’s important to understand their rise. Private markets’ growth has implications for stocks and bonds.

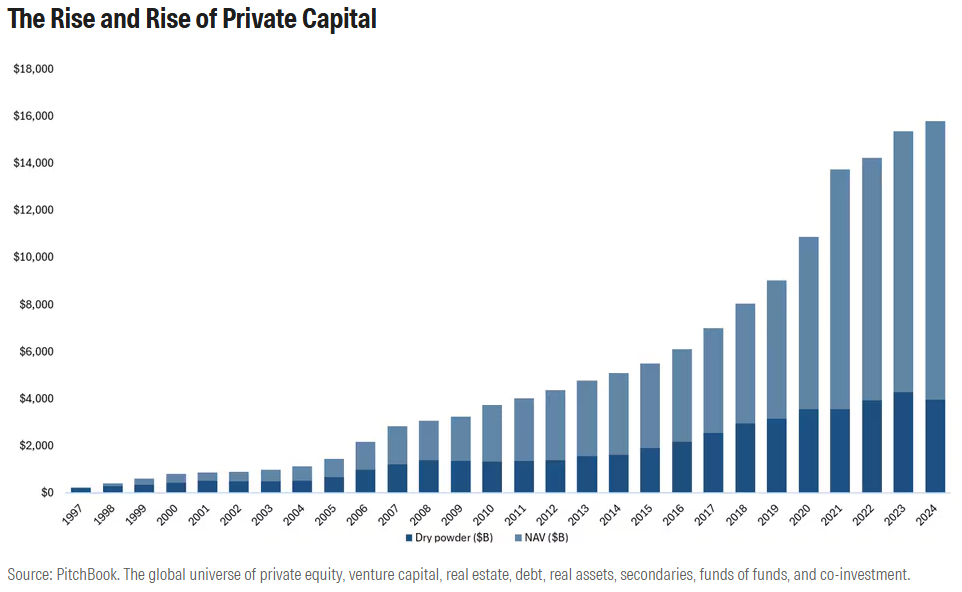

Putting $16 Trillion to Work

According to my colleagues at PitchBook, private capital is in the neighborhood of $16 trillion. Growth in private equity, venture capital, private debt, and other such funds has been truly astounding.

Where is this money coming from? It’s now common for institutional asset owners to allocate 15%, 20%, or even 30% of their portfolios to private market investments. An approach pioneered by the Yale University Endowment has been widely copied.

With abundant funding from private capital, companies can avoid the scrutiny, reporting, and regulation that come with publicly listing. US legislation like Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank made it even harder to be public, while the 2012 Jobs Act made it easier to be private. Proposals to reduce the frequency of public company reporting target the imbalance.

Perhaps you associate private market investments with 2% management fees and 20% performance fees, 10-year lockup periods, and lots of leverage. Perhaps you think private equity “plunders” and “pillages.” Many have no interest, even in cheaper and more liquid versions. That’s fine. Just be aware that private markets’ growth has implications. Here are three reasons for public market investors to care.

1) A Smaller Opportunity Set

The number of public companies has declined. According to the Center for Research in Security Prices, there were more than 7,000 publicly traded US companies in 1998. Today, it’s more like 4,000.

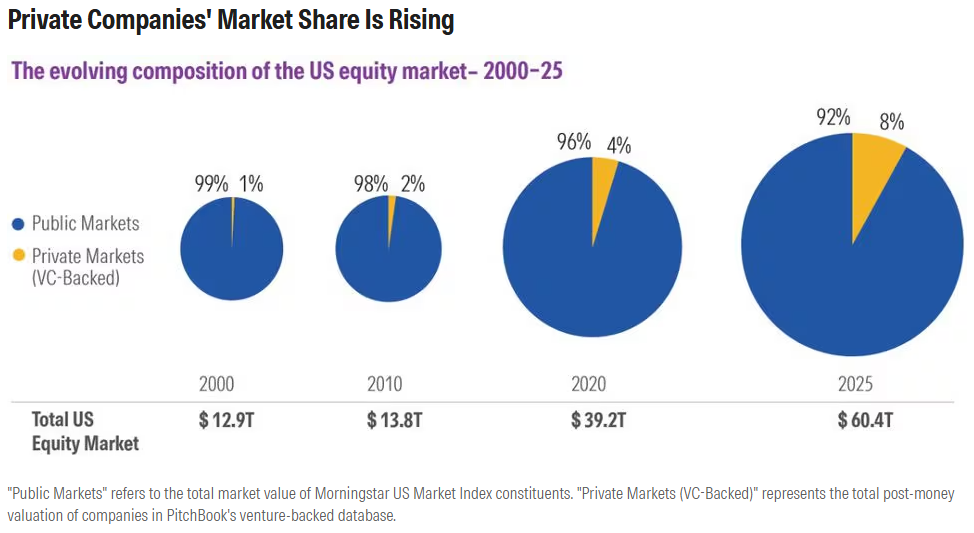

Back in the late 1990s internet bubble, you needed little more than a domain name and some “eyeballs” for an IPO. These days, companies stay private for years before going public, if at all. Klarna KLAR, the Swedish buy now, pay later provider that recently started trading in the US, was founded in 2005. Meanwhile, nearly 1,400 private companies have achieved “unicorn” status—valued at more than $1 billion. According to estimates by Morningstar Indexes and PitchBook, roughly 8% of total US equity value sits in companies backed by venture capital.

Who cares? Hasn’t the US stock market produced phenomenal returns in recent years, thanks in no small part to public companies like Meta Platforms META and Alphabet GOOGL that were once venture capital-backed startups? Sure, but a shrunken opportunity set will matter to some investors. I recently wrote about thematic investing and mentioned that private companies may sit on the leading edge of some growth trends. For example, investing in the business of space exploration is limited if you can’t access the category leader SpaceX. Public companies like Nvidia NVDA, Microsoft MSFT, and Alphabet are obviously big in artificial intelligence, but there are also key players on the private side, including OpenAI, xAI, and Anthropic. When it comes to financial technology, Stripe and Revolut are leaders. The list goes on. It can be argued that thematic opportunities can’t be fully captured without including private companies.

To represent the opportunity set across the spectrum, we recently launched the Morningstar PitchBook US Modern Market 100 Index, containing 90 public companies and 10 private ones.

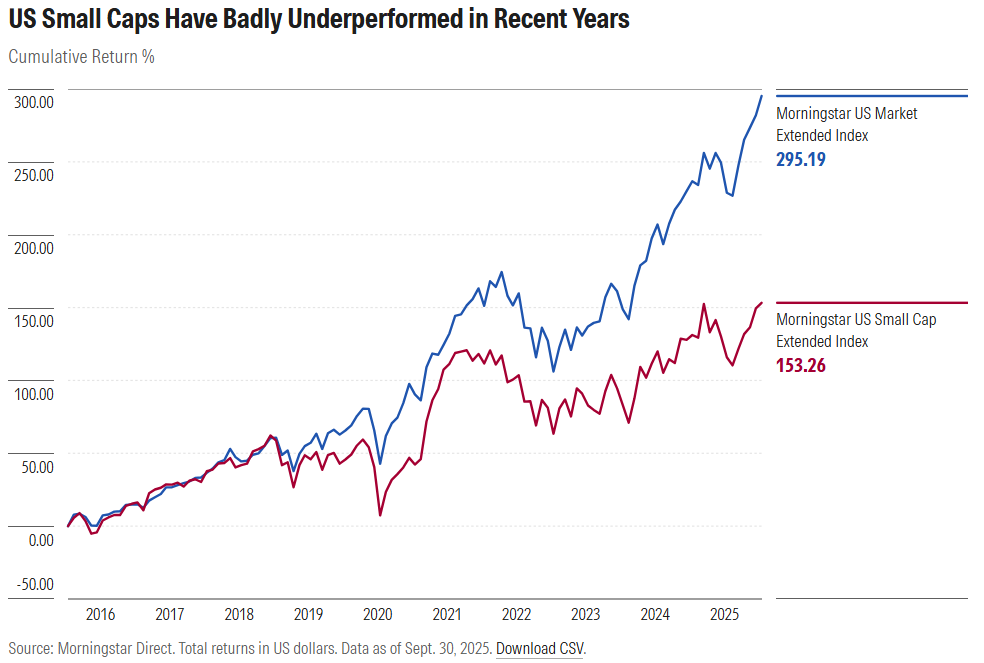

2) Small-Cap Stocks May Be Suffering

My colleague Zachary Evens recently published fascinating research, summarized in this article, contemplating whether private markets’ growth has contributed to the struggles of US small-cap stocks. Stocks in the bottom 10% of the market, as represented by the Morningstar US Small Cap Extended Index, have badly underperformed the overall US equity market in recent years. Small caps have defied the conventional wisdom by lagging in both up and down markets, rising and falling interest rate environments, and periods of economic expansion and contraction.

What’s the connection between private markets and public small-cap stocks? Morningstar’s Evens cites “a reduction in the number of public companies eligible for small-cap stock indexes, and a deterioration of the aggregate growth potential and relative quality of those companies.” He also mentions buyouts of public small caps.

I’m reminded of an interview we conducted last year with small-cap investor Charlie Dreifus for Morningstar’s The Long View podcast. At several points during the conversation, Dreifus named portfolio holdings that had been taken private. Computer Services was one example. Encore Wire was another.

Could some of the higher-quality public small caps be going private (in addition to potentially great small caps staying private)? Morningstar small-cap indexes certainly fall well short of the broad market on measures of profitability like net margins and return on invested capital.

It’s hard to definitively link the underperformance of small caps to the rise of private markets. Small caps can also get cheap enough to carry upside. But the asset class may be fundamentally altered. As Evens writes: “Tomorrow’s big stocks may never exist as a small-cap company.”

3) High-Yield Bonds Losing Share to Bank Loans and Private Debt

Readers who remember the 1980s might recall “corporate raiders” financing “leveraged buyouts” through “junk bonds.” Borrowing to fund mergers and acquisitions and other activities has only expanded. But the terminology has gone through rebranding, and new mechanisms are in use.

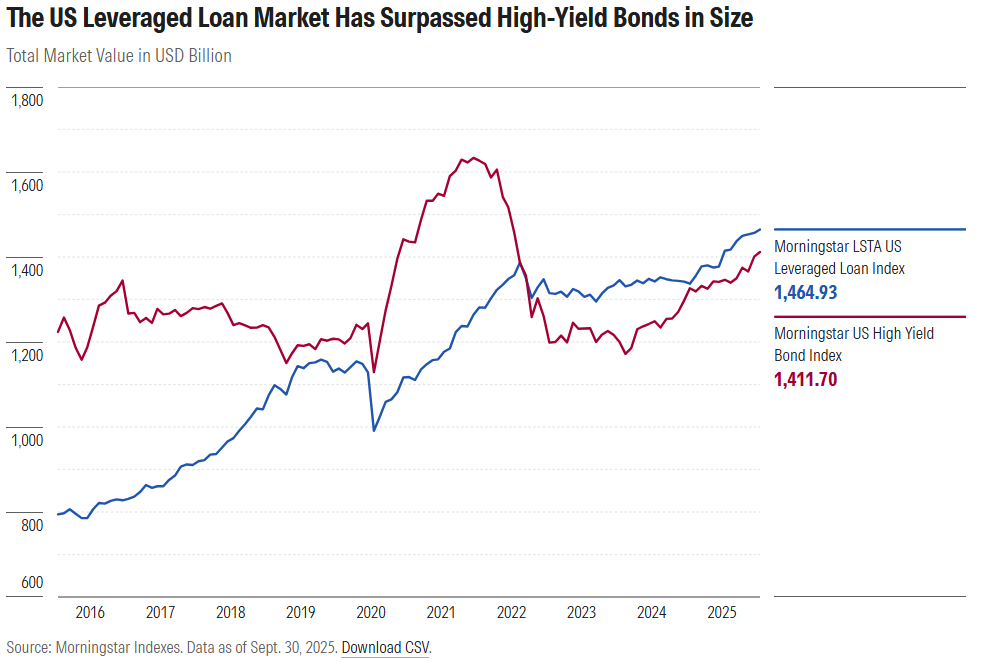

“High-yield bonds,” as they’re now known, are no longer the preferred debt instrument for “private equity” investors. Broadly syndicated bank loans, typically involving dozens of lenders, are often used to fund buyouts. For example, video game maker Electronic Arts EA recently announced it would be taken private by a consortium including Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund, Silver Lake, and Affinity Partners. The deal was backed by $20 billion in debt financing from JPMorgan.

The Morningstar LSTA US Leveraged Loan Index, which represents the universe for these sub-investment-grade transactions, now exceeds the Morningstar US High-Yield Bond Index in total market value. Over the past 10 years, the loan market has doubled in size.

Loans are technically private. They were once offered to retail investors through interval funds. But their broad syndication has made them liquid enough to underpin exchange-traded funds since 2011. The asset class has moved from niche to mainstream, with Morningstar research suggesting that it can contribute to a diversified fixed-income portfolio allocation. Loans are also used to proxy private debt.

Meanwhile, private debt is booming. Available to retail investors through semiliquid funds, it is thought to be larger than high yield and bank loans in market size. Credit risk is a feature of the asset class, as are fat income streams.

High-yield bonds, for their part, have gone in the other direction. Their credit quality has improved, and recovery rates have risen. As a result, yields have fallen. Similar to small-cap stocks, the asset class isn’t what it once was. According to the Morningstar Diversification Landscape Report, high-yield bonds carry fairly high correlations to both the broad bond and broad equity markets.

Private Capital Will Be Reshaping Investing for Years to Come

In the PitchBook private capital data above, did you notice “dry powder” in the neighborhood of $4 trillion? Those are assets committed but not yet deployed. Even if private capital growth falls short of the $24 trillion by 2029 projected by PitchBook, it will be looking for a home for years to come.

Private equity, venture capital, and private debt will continue to compete with public stock and bond markets for capital formation. No matter your view on their relative merits, the impact of private markets’ growth can’t be ignored.

©2025 Morningstar. All Rights Reserved. The information, data, analyses and opinions contained herein (1) include the proprietary information of Morningstar, (2) may not be copied or redistributed, (3) do not constitute investment advice offered by Morningstar, (4) are provided solely for informational purposes and therefore are not an offer to buy or sell a security, and (5) are not warranted to be correct, complete or accurate. Morningstar has not given its consent to be deemed an "expert" under the federal Securities Act of 1933. Except as otherwise required by law, Morningstar is not responsible for any trading decisions, damages or other losses resulting from, or related to, this information, data, analyses or opinions or their use. References to specific securities or other investment options should not be considered an offer (as defined by the Securities and Exchange Act) to purchase or sell that specific investment. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Before making any investment decision, consider if the investment is suitable for you by referencing your own financial position, investment objectives, and risk profile. Always consult with your financial advisor before investing.

Indexes are unmanaged and not available for direct investment.

Morningstar indexes are created and maintained by Morningstar, Inc. Morningstar® is a registered trademark of Morningstar, Inc.