Doesn’t this seem an odd time for companies to be repurchasing their own shares? By many measures, the broad US stock market looks pricey. My favorite indicator, Morningstar’s market-level fair value, which aggregates company-specific valuations assigned by our equity analysts, shows US stocks trading at a premium.

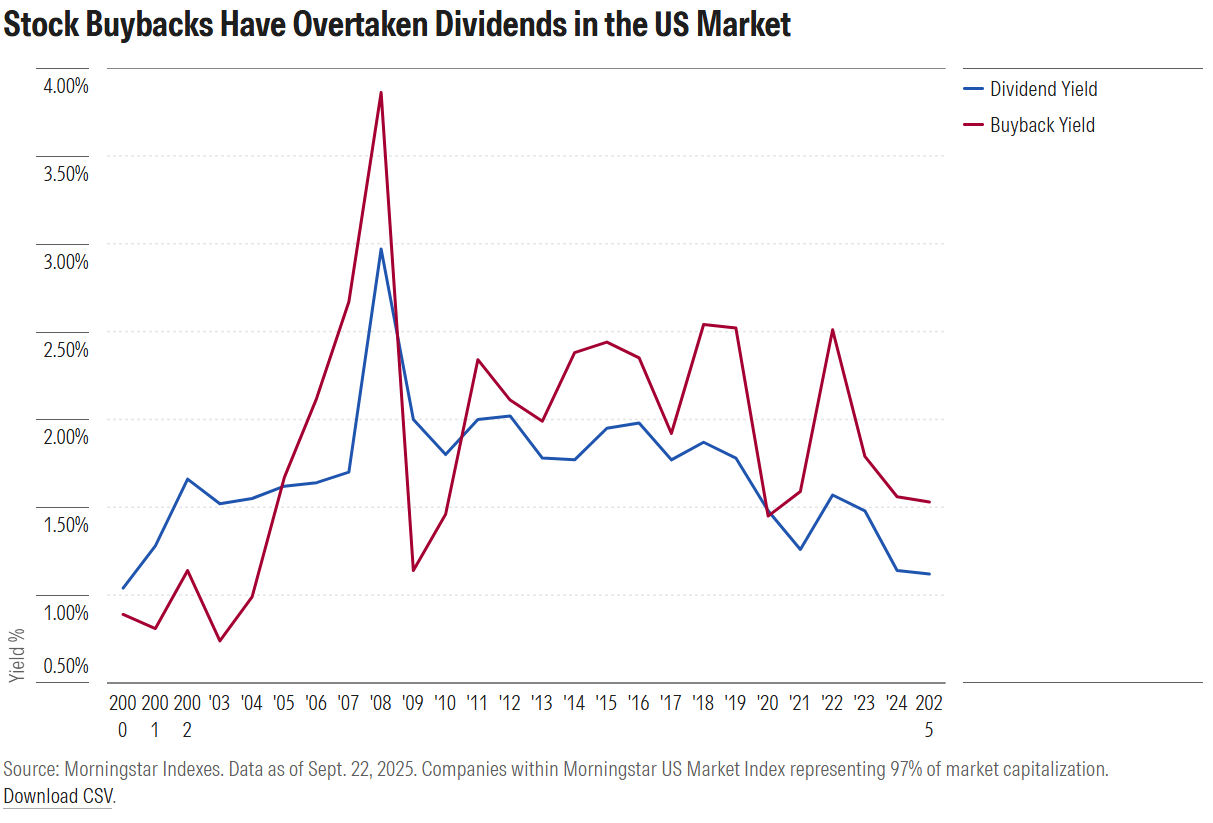

Despite elevated prices, companies in the Morningstar US Market Index have spent more than $1 trillion on stock buybacks for the trailing 12 months through September 2025. Meanwhile, they’ve only devoted $740 billion to dividends. Shouldn’t companies only use excess cash to repurchase shares when they’re trading at a discount?

I contacted my Morningstar Indexes colleague Aniket Gor, who does a lot of research related to stock buybacks. His data and insights helped put the 2025 buyback boom in both historical and global context, shedding light on the question: Are stock buybacks good for investors?

What’s Fueling the Stock Buyback Boom?

Corporate America splurging on buybacks is nothing new. Share repurchases eclipsed dividends as a means of returning cash to shareholders 20 years ago in the US and have mostly led ever since. According to Aniket’s research, roughly two thirds of the 1,202 current constituents of the Morningstar US Market Index repurchased shares over the last year. Twenty years ago, just 22% of companies in the index did buybacks.

Why has this happened? One answer lies in the adage: “Buybacks are like dating; dividends are like marriage.” Repurchasing shares isn’t the same commitment as a quarterly cash payout to shareholders. A company can buy back its shares when it sees them as offering good value and/or when it’s feeling flush. By contrast, the market typically punishes the stocks of businesses that reduce, suspend, or eliminate dividends.

Tax efficiency is another commonly cited advantage of buybacks. Dividends are taxed, whereas the shareholders of buyback stocks only pay tax if they sell. Another factor related to policy and regulation was a 1982 Securities and Exchange Commission rule that softened restrictions on companies purchasing their own shares.

Skeptics, for their part, see buybacks as lacking the cash-in-hand appeal that dividends offer. Irregular share repurchases don’t instill discipline on corporate management like the pressure of delivering a quarterly payout. Some question the motives behind buybacks, speculating that managers and directors are just trying to enrich themselves by boosting earnings per share. Buybacks have even come in for criticism from politicians who say cash should be spent on reinvestment, such as research and development.

It should be noted that buybacks can be accompanied by new share issuance. Such dilution undermines the benefits of increasing shareholders’ fractional ownership. According to Aniket’s research, 9% of US companies that bought back their own shares over the past year also issued new ones.

Implications of the Stock Buyback Boom

Do buybacks signal anything about stock prices? In theory, share repurchases are a sign of confidence from those most intimately familiar with a business. Corporate managers and directors possess inside information by definition and seem well-placed to value their own shares. A spate of buybacks after the October 1987 “Black Monday” crash and in the wake of the market downturn following the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks suggests that managers took advantage of selloffs to scoop up their own shares on the cheap.

My colleague Aniket has surveyed the academic literature (including this piece from the Handbook of the Economics of Finance) and has also run some tests of his own. He found that the shares of companies conducting buybacks have outperformed companies that don’t repurchase their own shares. This makes sense given their financial strength. But on whether companies buying back shares consistently outperform, the overall market is less clear. They did over some time periods but not others.

When I look at the market-level data over the past several years, no clear trend emerges. I see buybacks surging in 2019, which is curious from a timing perspective because the Morningstar US Market Index rose 31% that year. More understandable is the decline in share repurchases amid 2020’s “pandemic panic.” Companies can be forgiven for hoarding cash in uncertain times. That year also brought lots of dividend cuts. Another surge in buybacks came amid the buoyant market of 2021. Then, buybacks rose in 2022, while stocks plunged, which could be seen as taking advantage of a pullback. To me, buybacks look more like cash burning a hole in companies’ pockets than valuation calls.

The most obvious consequence of the buyback boom is a decline in dividends. Before the 2000s, the broad US stock market’s dividend yield ranged between 3% and 6%. It is now well below 2%.

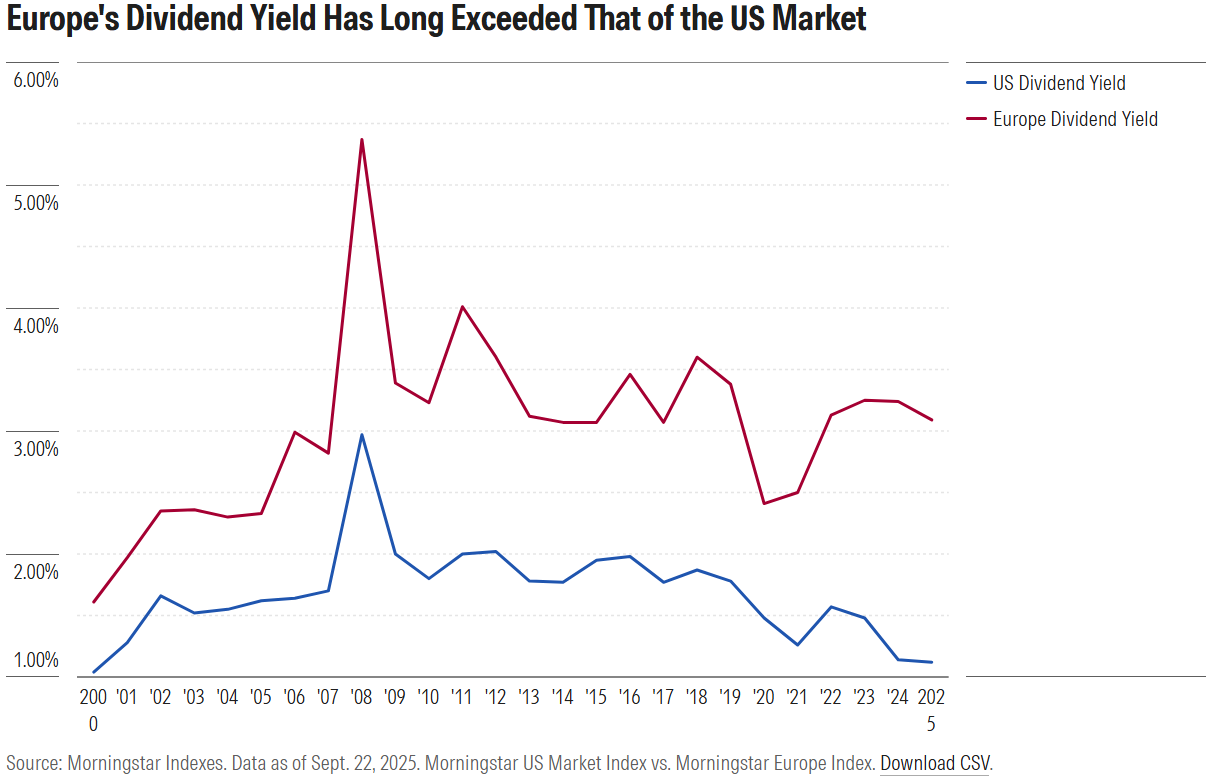

Meanwhile, in Europe, dividends remain more popular than buybacks. Outside North America, dividends are often paid out opportunistically, and cuts in payouts aren’t punished as severely. In Europe, buybacks don’t enjoy quite the same tax advantage they do in the US. For equity-income investors interested in international dividend funds, my colleague Todd Trubey highlighted some high-yielding picks. Just be mindful of their tax implications.

The Total Shareholder Yield Concept

Academic theory teaches that investors should be agnostic as to how cash is returned. In any case, buybacks versus dividends is something of a false dichotomy. Many companies do both.

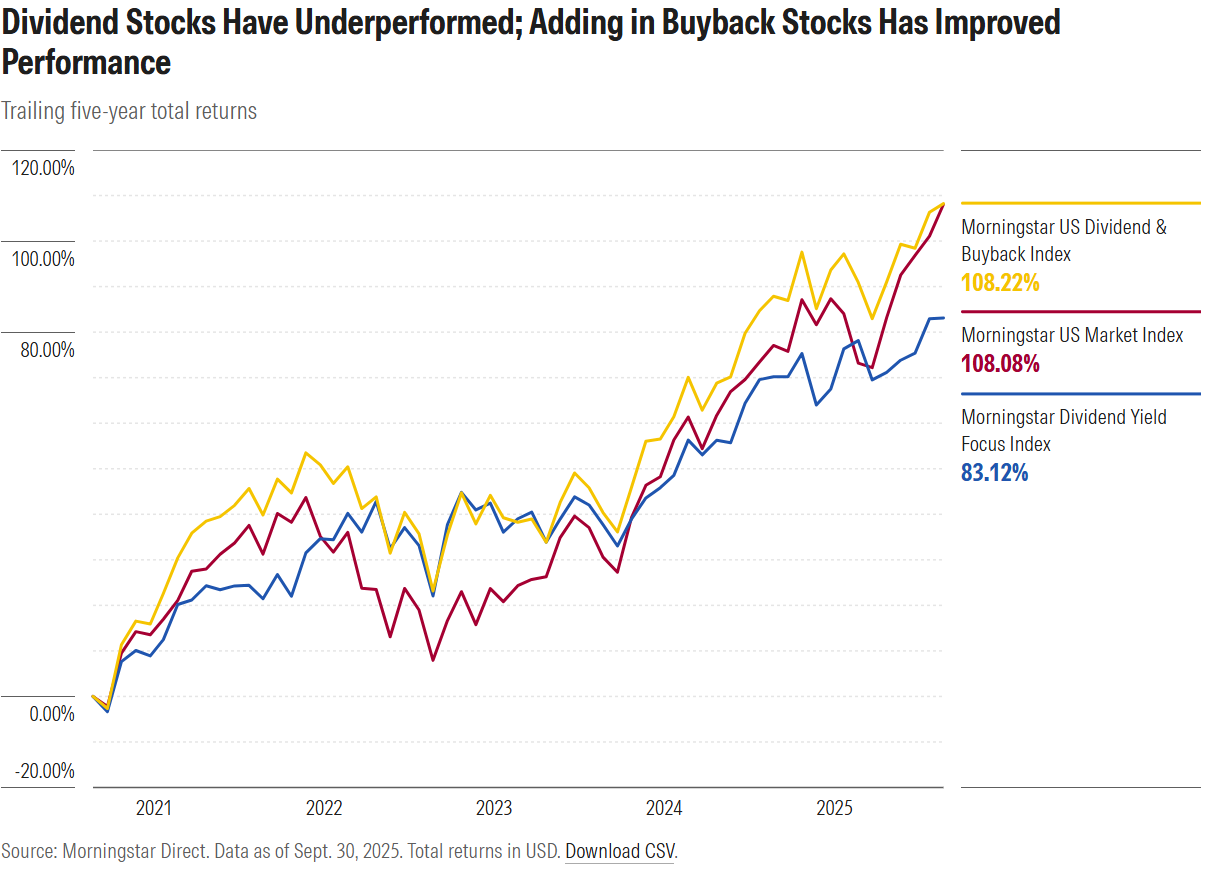

The concept of “total shareholder yield” recognizes the new reality. Given the rise of buybacks in the US, yield metrics and valuation tools that consider dividends alone could be obsolete. My colleague Philip Straehl of Morningstar Investment Management has done work on using a total payout model to value the market.

The Morningstar US Dividend and Buyback Index includes both kinds of yielders. Compared with a dividend-only index, it broadens the opportunity set and more closely resembles the broad US market. Its performance has certainly been more marketlike over the past five years, in contrast to most dividend indexes, which have underperformed. Including tech companies that are dividend-light but buyback-heavy has been a winning strategy.

What Does the Stock Buyback Boom Mean for Investors?

Capital allocation is arguably the most important task facing corporate management. Should a company be successful enough to earn profits, it must answer a key question: How should cash on the balance sheet be deployed? The optimal mix of growth-focused reinvestment, acquisitions, saving or debt reduction, dividends, and share repurchases is a holy grail pursued by executives and directors.

“When stock can be bought below a business’ value, it is probably the best use of cash,” says Warren Buffett. That’s a key condition, though. Buybacks taking place amid stock market rallies raise eyebrows. So do companies with systematic buyback programs that don’t seem to consider valuation at all.

Dividends, on the other hand, maintain their loyal following, in large part because of their regularity. They are treasured for reasons that go beyond income. To some, they represent the most tangible link between a share of stock and an underlying business’ cash flows.

But market dynamics have changed. Aggregate buyback dollars in the US are on track to exceed dividend dollars for the fifth straight year in 2025. The new paradigm even prompted me to ask: Does Dividend Investing Still Work?

That remains an open question. What’s clearer is that equity-income investing has become more challenging from an income perspective. It’s also a real bet against the broad stock market. “Total shareholder yield” is a useful concept for understanding cash redistribution holistically.

©2025 Morningstar. All Rights Reserved. The information, data, analyses and opinions contained herein (1) include the proprietary information of Morningstar, (2) may not be copied or redistributed, (3) do not constitute investment advice offered by Morningstar, (4) are provided solely for informational purposes and therefore are not an offer to buy or sell a security, and (5) are not warranted to be correct, complete or accurate. Morningstar has not given its consent to be deemed an "expert" under the federal Securities Act of 1933. Except as otherwise required by law, Morningstar is not responsible for any trading decisions, damages or other losses resulting from, or related to, this information, data, analyses or opinions or their use. References to specific securities or other investment options should not be considered an offer (as defined by the Securities and Exchange Act) to purchase or sell that specific investment. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Before making any investment decision, consider if the investment is suitable for you by referencing your own financial position, investment objectives, and risk profile. Always consult with your financial advisor before investing.

Indexes are unmanaged and not available for direct investment.

Morningstar indexes are created and maintained by Morningstar, Inc. Morningstar® is a registered trademark of Morningstar, Inc.